Against the Gods: Iris Murdoch on Truth, the Meaning of Goodness, and How Attention Unmasks the Universe

Original article by Maria Popova for The Marginalian

“When we really know something we feel we’ve always known it. Yet also it’s terribly distant, farther than any star… beyond the world, not in the clouds or in heaven, but a light that shows the world, this world, as it really is.”

When Nietzsche weighed our human notion of truth, he regarded it as “a movable host of metaphors, metonymies, and anthropomorphisms: in short, a sum of human relations which have been poetically and rhetorically intensified, transferred, and embellished.” This is true of truth in the human world, and this is where science and society differ. The disparity is the reason why the scientific perspective can offer such gladsome calibration and consolation for our human struggles.

In the world of science, we endeavor to uncover fundamental laws and elemental truths indifferent to our opinions of them — those selfsame truths and laws that made us and govern the electrical impulses coursing through our cortices at 100 meters per second to forge the thought-patterns of opinion. But in the human world where we live, we swirl in the movable host of human relations and rationalizations, vaguely aware that there is no universal truth and therefore no universal good, because every utopia is built on someone else’s back. We devise frameworks for righting our relations, which we call morality, but in our helpless confusion about what goodness is, we too readily mistake certainty for truth and self-righteousness for truth, then lash one another with our certitudes and rightneousnesses, mistaking the lashing for the light of morality.

When our species was younger and more frightened of reality, myths and religions have provided the comfort of easy causalities and easy moralities to salve the confusions of complexity. But as the epoch of scientific discovery began disproving some of those sacred certainties — first ejecting us from the placid plane of the flat Earth, then from our self-soothing centrality in the Solar System, then from our grandiose exceptionalism in the order of living things, then from our galactic exceptionalism — the moral certitudes about goodness also came unloosed, for they too were built upon the same self-righteous foundation as the old delusions about the geometry of the universe and the immutability of life-forms.

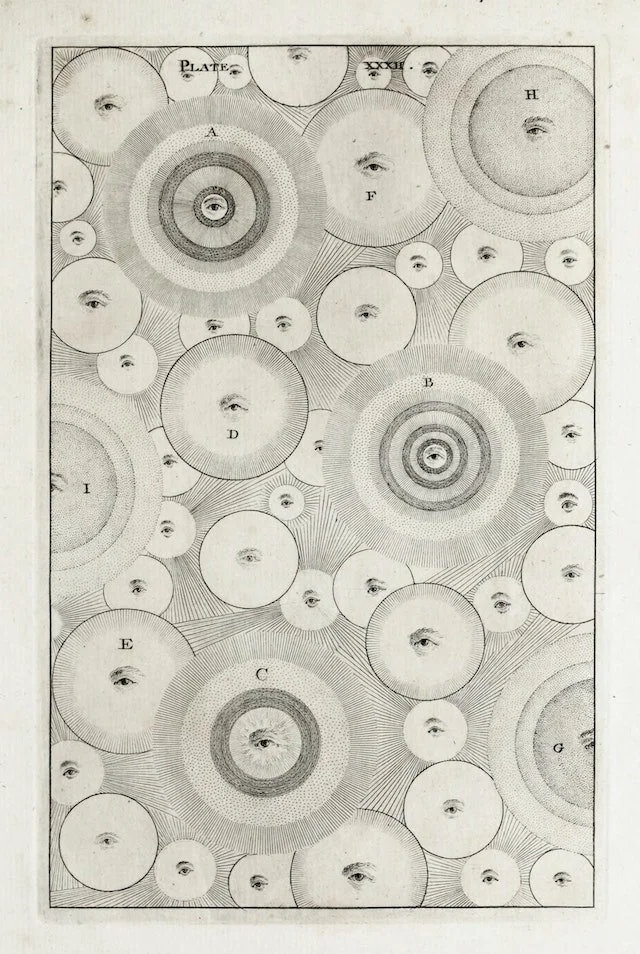

Art from Thomas Wright’s An Original Theory or New Hypothesis of the Universe, 1750. (Available as a print.)

The dazzling-minded Iris Murdoch (July 15, 1919–February 8, 1999) took up these questions in her play Above the Gods — one of two Platonic dialogues she wrote in the 1980s, later included in the posthumous Murdoch anthology Existentialists and Mystics: Writings on Philosophy and Literature (public library), which remains one of the finest works of writing and thinking I have encountered.

Set in Athens in the late fifth century B.C. and structured as a conversation between a sixty-something Socrates, a twenty-something Plato, and four fictional Greek youths, the dialogue tussles with the question of whether the age of science has knelled the death toll of religion and, if so, where this leaves our search for truth and our longing for goodness — that elemental hunger for the ultimate meaning of reality, for our responsibility to reality.

Read full article here, on The Marginalian